Lenny Abrahamson’s Frank offers a refreshingly honest take on the standard rise-and-fall journey of a band, defying convention in its approach towards the creative process. In doing so, Frank celebrates the eccentricities of its artists without glamorising them, inverting cliché ideas of tortured genius through a bizarre, vivid and insightful journey through the creative process and the psychology behind it.

Following aspiring but creatively-bereft musician Jon’s (Domnhall Gleeson) chance encounter with a keyboard player-less band (“the Soronpfrbs”), he is introduced to the mysterious Frank (Michael Fassbender) – a singer-songwriter whose head is sealed inside a paper mache mask at all times. Soon, however, Jon realises Frank is not just a freak in a costume, but a brilliant and visionary artist. As he joins Frank’s equally eccentric entourage, Jon desperately tries to undergo the same kind of trauma that will finally allow him to see the world as Frank does…

The focus here is definitely not on the rock n’roll, but neither is it on the sex and drugs. Rather, the thrust of Frank is creativity itself, with the Soronpfrbs spending much of the film isolated in a lake-side retreat undergoing all sorts of insane trials and tribulations at the behest of Frank – from intense physical training, to inventing their own musical language. Nevertheless, the band all follow Frank, and as Jon increasingly struggles to find his creative spark, the film is challenging us just as Frank’s talent challenges Jon: is creativity a natural gift only a few possess? Or is it a result of your experiences?

This all boils down to whether creativity can be emulated or if you are just born with it. What Frank highlights through this approach to the creative process is that there is often this assumption in musical spheres that creativity must come from an external force – be that drugs, sex, or (as is the case here) mental trauma. Certainly, such factors can inspire creativity, but the ultimate source of creativity comes from within; you don’t have a parent die then suddenly become Bob Dylan.

Really, this is a problem of correlation over causation; that multiple artists seemingly share such personal trauma does not mean said trauma is the source of their talent or creativity. In fact, these external influences often hinder creativity rather than boost it – as much as people like to romanticise Syd Barrett as a tortured genius, the truth is that drug use ultimately destroyed his ability to create (and indeed function as a human being). Likewise, Frank’s mental problems are revealed to have developed after his creative talents, and to have only ever hindered him in musically expressing himself.

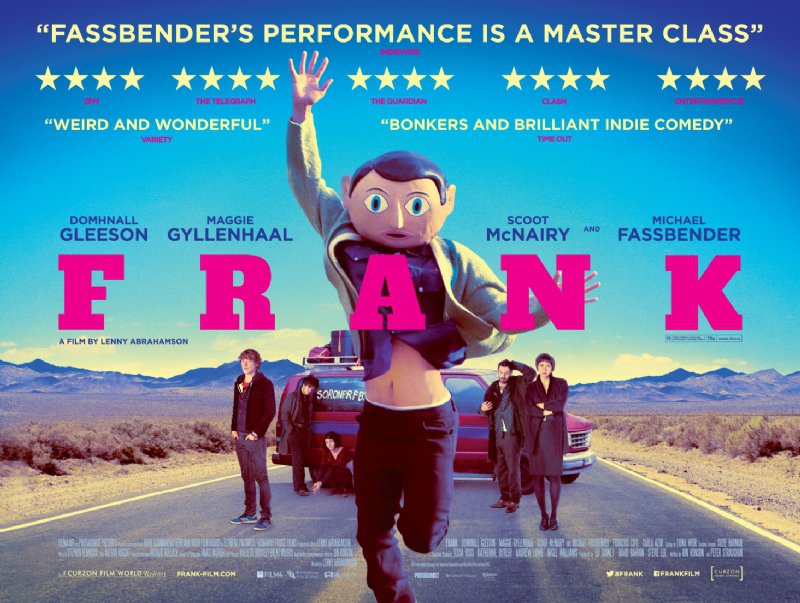

Fassbender’s performance as Frank is no less vivid and brilliant than the character himself

It’s a testament to Fassbender’s ability that he is able to anchor the entire film in a performance that is always compelling, and moreover remarkably multi-faceted, showing the duality between brilliance and madness, between eccentricity and vulnerability. Acting as the perfect foil to Gleeson’s self-centred but relatable Jon, Fassbender’s Frank shows a character fascinated with the fleeting and very much in-the-moment, who can create art with ease but lacks the focus or maturity to package this in a way that is easily accessible.

Crucially, Fassbender is able to show by the time the credits roll that Frank has the creativity Jon lacks but equally doesn’t possess Jon’s desire for fame and fortune. For him, the Soronpfrbs aren’t a means to revolutionise music or change the world, just a way of expressing himself alongside his friends in a world full of people who don’t understand him, and when Jon tries to exploit Frank’s talent for his own ends, it becomes clear that creativity has to be achieved on its own terms; someone like Frank can’t be creative when tied to a commercially-palatable tether. In this way, Frank represents creativity in its pure and unrefined form, whereas Jon represents the bluster and excess of people who wrongly misunderstand creativity as something you can emulate and control through formula.

There’s not really much more to Frank than this, but there doesn’t need to be. You don’t need a big budget, layers of visual effects or a two hour run-time to make a great film – just a great idea that is both intelligently conceived and executed. To put it another way: you can’t compensate for a lack of creativity with any amount of explosions or horn of dooms. Neither can you emulate it simply by surrounding yourself with the best writers, the best technology or the best cinematographers – because even if external factors may inspire you in one direction or another, the creative spark must ultimately come from within. And guess what? If you start out with nothing to say, your film is probably going to end up with the same problem.

Perhaps none of this is sending the most inspirational message for budding artists out there. However, the message Frank conveys doesn’t dispose of ideas of improvement and progression, it simply shows that they can only take you so far. Not everybody can be Stanley Kubrick or Jimi Hendrix; not everybody can be Frank. Some artists just operate at a level too far beyond their contemporaries for anybody to ever match. Pointing this out isn’t a criticism of self-improvement, but a celebration of individuality, only making these rare few creative sparks – much like Frank itself is in a sea of uninspired sequels and muddled messages – all the more precious to us.

Verdict: 10/10